SQL with Python

OverviewQuestions:Objectives:

How can I access databases from programs written in Python?

Requirements:

Write short programs that execute SQL queries.

Trace the execution of a program that contains an SQL query.

Explain why most database applications are written in a general-purpose language rather than in SQL.

- Foundations of Data Science

- Advanced SQL: tutorial hands-on

Time estimation: 45 minutesLevel: Intermediate IntermediateSupporting Materials:Last modification: Oct 19, 2022

Best viewed in a Jupyter NotebookThis tutorial is best viewed in a Jupyter notebook! You can load this notebook one of the following ways

Launching the notebook in Jupyter in Galaxy

- Instructions to Launch JupyterLab

- Open a Terminal in JupyterLab with File -> New -> Terminal

- Run

wget https://training.galaxyproject.org/training-material/topics/data-science/tutorials/sql-python/data-science-sql-python.ipynb- Select the notebook that appears in the list of files on the left.

Downloading the notebook

- Right click one of these links: Jupyter Notebook (With Solutions), Jupyter Notebook (Without Solutions)

- Save Link As..

CommentThis tutorial is significantly based on the Carpentries Databases and SQL lesson, which is licensed CC-BY 4.0.

Abigail Cabunoc and Sheldon McKay (eds): “Software Carpentry: Using Databases and SQL.” Version 2017.08, August 2017, github.com/swcarpentry/sql-novice-survey, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.838776

Adaptations have been made to make this work better in a GTN/Galaxy environment.

AgendaIn this tutorial, we will cover:

For this tutorial we need to download a database that we will use for the queries.

!wget -c http://swcarpentry.github.io/sql-novice-survey/files/survey.db

Programming with Databases - Python

Let’s have a look at how to access a database from a general-purpose programming language like Python. Other languages use almost exactly the same model: library and function names may differ, but the concepts are the same.

Here’s a short Python program that selects latitudes and longitudes

from an SQLite database stored in a file called survey.db:

import sqlite3

connection = sqlite3.connect("survey.db")

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute("SELECT Site.lat, Site.long FROM Site;")

results = cursor.fetchall()

for r in results:

print(r)

cursor.close()

connection.close()

The program starts by importing the sqlite3 library.

If we were connecting to MySQL, DB2, or some other database,

we would import a different library,

but all of them provide the same functions,

so that the rest of our program does not have to change

(at least, not much)

if we switch from one database to another.

Line 2 establishes a connection to the database. Since we’re using SQLite, all we need to specify is the name of the database file. Other systems may require us to provide a username and password as well. Line 3 then uses this connection to create a cursor. Just like the cursor in an editor, its role is to keep track of where we are in the database.

On line 4, we use that cursor to ask the database to execute a query for us.

The query is written in SQL,

and passed to cursor.execute as a string.

It’s our job to make sure that SQL is properly formatted;

if it isn’t,

or if something goes wrong when it is being executed,

the database will report an error.

The database returns the results of the query to us

in response to the cursor.fetchall call on line 5.

This result is a list with one entry for each record in the result set;

if we loop over that list (line 6) and print those list entries (line 7),

we can see that each one is a tuple

with one element for each field we asked for.

Finally, lines 8 and 9 close our cursor and our connection, since the database can only keep a limited number of these open at one time. Since establishing a connection takes time, though, we shouldn’t open a connection, do one operation, then close the connection, only to reopen it a few microseconds later to do another operation. Instead, it’s normal to create one connection that stays open for the lifetime of the program.

Queries in real applications will often depend on values provided by users. For example, this function takes a user’s ID as a parameter and returns their name:

import sqlite3

def get_name(database_file, person_id):

query = "SELECT personal || ' ' || family FROM Person WHERE id='" + person_id + "';"

connection = sqlite3.connect(database_file)

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute(query)

results = cursor.fetchall()

cursor.close()

connection.close()

return results[0][0]

print("Full name for dyer:", get_name('survey.db', 'dyer'))

We use string concatenation on the first line of this function to construct a query containing the user ID we have been given. This seems simple enough, but what happens if someone gives us this string as input?

dyer'; DROP TABLE Survey; SELECT '

It looks like there’s garbage after the user’s ID, but it is very carefully chosen garbage. If we insert this string into our query, the result is:

SELECT personal || ' ' || family FROM Person WHERE id='dyer'; DROP TABLE Survey; SELECT '';

If we execute this, it will erase one of the tables in our database.

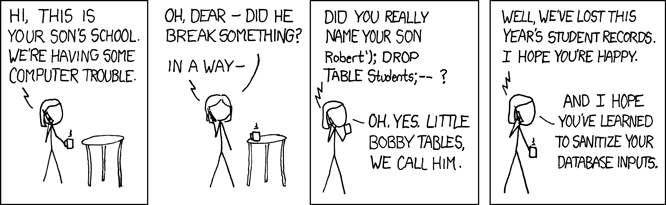

This is called an SQL injection attack, and it has been used to attack thousands of programs over the years. In particular, many web sites that take data from users insert values directly into queries without checking them carefully first. A very relevant XKCD that explains the dangers of using raw input in queries a little more succinctly:

Since a villain might try to smuggle commands into our queries in many different ways, the safest way to deal with this threat is to replace characters like quotes with their escaped equivalents, so that we can safely put whatever the user gives us inside a string. We can do this by using a prepared statement instead of formatting our statements as strings. Here’s what our example program looks like if we do this:

import sqlite3

def get_name(database_file, person_id):

query = "SELECT personal || ' ' || family FROM Person WHERE id=?;"

connection = sqlite3.connect(database_file)

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute(query, [person_id])

results = cursor.fetchall()

cursor.close()

connection.close()

return results[0][0]

print("Full name for dyer:", get_name('survey.db', 'dyer'))

The key changes are in the query string and the execute call.

Instead of formatting the query ourselves,

we put question marks in the query template where we want to insert values.

When we call execute,

we provide a list

that contains as many values as there are question marks in the query.

The library matches values to question marks in order,

and translates any special characters in the values

into their escaped equivalents

so that they are safe to use.

We can also use sqlite3’s cursor to make changes to our database,

such as inserting a new name.

For instance, we can define a new function called add_name like so:

import sqlite3

def add_name(database_file, new_person):

query = "INSERT INTO Person (id, personal, family) VALUES (?, ?, ?);"

connection = sqlite3.connect(database_file)

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute(query, list(new_person))

cursor.close()

connection.close()

def get_name(database_file, person_id):

query = "SELECT personal || ' ' || family FROM Person WHERE id=?;"

connection = sqlite3.connect(database_file)

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute(query, [person_id])

results = cursor.fetchall()

cursor.close()

connection.close()

return results[0][0]

# Insert a new name

add_name('survey.db', ('barrett', 'Mary', 'Barrett'))

# Check it exists

print("Full name for barrett:", get_name('survey.db', 'barrett'))

Note that in versions of sqlite3 >= 2.5, the get_name function described

above will fail with an IndexError: list index out of range,

even though we added Mary’s

entry into the table using add_name.

This is because we must perform a connection.commit() before closing

the connection, in order to save our changes to the database.

import sqlite3

def add_name(database_file, new_person):

query = "INSERT INTO Person (id, personal, family) VALUES (?, ?, ?);"

connection = sqlite3.connect(database_file)

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute(query, list(new_person))

cursor.close()

connection.commit()

connection.close()

def get_name(database_file, person_id):

query = "SELECT personal || ' ' || family FROM Person WHERE id=?;"

connection = sqlite3.connect(database_file)

cursor = connection.cursor()

cursor.execute(query, [person_id])

results = cursor.fetchall()

cursor.close()

connection.close()

return results[0][0]

# Insert a new name

add_name('survey.db', ('barrett', 'Mary', 'Barrett'))

# Check it exists

print("Full name for barrett:", get_name('survey.db', 'barrett'))

Question: Filling a Table vs. Printing ValuesWrite a Python program that creates a new database in a file called

original.dbcontaining a single table calledPressure, with a single field calledreading, and inserts 100,000 random numbers between 10.0 and 25.0. How long does it take this program to run? How long does it take to run a program that simply writes those random numbers to a file?import sqlite3 # import random number generator from numpy.random import uniform random_numbers = uniform(low=10.0, high=25.0, size=100000) connection = sqlite3.connect("original.db") cursor = connection.cursor() cursor.execute("CREATE TABLE Pressure (reading float not null)") query = "INSERT INTO Pressure (reading) VALUES (?);" for number in random_numbers: cursor.execute(query, [number]) cursor.close() connection.commit() # save changes to file for next exercise connection.close()For comparison, the following program writes the random numbers into the file

random_numbers.txt:from numpy.random import uniform random_numbers = uniform(low=10.0, high=25.0, size=100000) with open('random_numbers.txt', 'w') as outfile: for number in random_numbers: # need to add linebreak \n outfile.write("{}\n".format(number))

Question: Filtering in SQL vs. Filtering in PythonWrite a Python program that creates a new database called

backup.dbwith the same structure asoriginal.dband copies all the values greater than 20.0 fromoriginal.dbtobackup.db. Which is faster: filtering values in the query, or reading everything into memory and filtering in Python?The first example reads all the data into memory and filters the numbers using the if statement in Python.

import sqlite3 connection_original = sqlite3.connect("original.db") cursor_original = connection_original.cursor() cursor_original.execute("SELECT * FROM Pressure;") results = cursor_original.fetchall() cursor_original.close() connection_original.close() connection_backup = sqlite3.connect("backup.db") cursor_backup = connection_backup.cursor() cursor_backup.execute("CREATE TABLE Pressure (reading float not null)") query = "INSERT INTO Pressure (reading) VALUES (?);" for entry in results: # number is saved in first column of the table if entry[0] > 20.0: cursor_backup.execute(query, entry) cursor_backup.close() connection_backup.commit() connection_backup.close()In contrast the following example uses the conditional

SELECTstatement to filter the numbers in SQL. The only lines that changed are in line 5, where the values are fetched fromoriginal.dband the for loop starting in line 15 used to insert the numbers intobackup.db. Note how this version does not require the use of Python’s if statement.import sqlite3 connection_original = sqlite3.connect("original.db") cursor_original = connection_original.cursor() cursor_original.execute("SELECT * FROM Pressure WHERE reading > 20.0;") results = cursor_original.fetchall() cursor_original.close() connection_original.close() connection_backup = sqlite3.connect("backup.db") cursor_backup = connection_backup.cursor() cursor_backup.execute("CREATE TABLE Pressure (reading float not null)") query = "INSERT INTO Pressure (reading) VALUES (?);" for entry in results: cursor_backup.execute(query, entry) cursor_backup.close() connection_backup.commit() connection_backup.close()

Question: Generating Insert StatementsOne of our colleagues has sent us a CSV file containing temperature readings by Robert Olmstead, which is formatted like this:

Taken,Temp 619,-21.5 622,-15.5Write a small Python program that reads this file in and prints out the SQL

INSERTstatements needed to add these records to the survey database. Note: you will need to add an entry for Olmstead to thePersontable. If you are testing your program repeatedly, you may want to investigate SQL’sINSERT or REPLACEcommand.

Key points

General-purpose languages have libraries for accessing databases.

To connect to a database, a program must use a library specific to that database manager.

These libraries use a connection-and-cursor model.

Programs can read query results in batches or all at once.

Queries should be written using parameter substitution, not string formatting.

Frequently Asked Questions

Have questions about this tutorial? Check out the tutorial FAQ page or the FAQ page for the Foundations of Data Science topic to see if your question is listed there. If not, please ask your question on the GTN Gitter Channel or the Galaxy Help ForumFeedback

Did you use this material as an instructor? Feel free to give us feedback on how it went.

Did you use this material as a learner or student? Click the form below to leave feedback.

Citing this Tutorial

- The Carpentries, Helena Rasche, Avans Hogeschool, 2022 SQL with Python (Galaxy Training Materials). https://training.galaxyproject.org/training-material/topics/data-science/tutorials/sql-python/tutorial.html Online; accessed TODAY

- Batut et al., 2018 Community-Driven Data Analysis Training for Biology Cell Systems 10.1016/j.cels.2018.05.012

Congratulations on successfully completing this tutorial!@misc{data-science-sql-python, author = "The Carpentries and Helena Rasche and Avans Hogeschool", title = "SQL with Python (Galaxy Training Materials)", year = "2022", month = "10", day = "19" url = "\url{https://training.galaxyproject.org/training-material/topics/data-science/tutorials/sql-python/tutorial.html}", note = "[Online; accessed TODAY]" } @article{Batut_2018, doi = {10.1016/j.cels.2018.05.012}, url = {https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cels.2018.05.012}, year = 2018, month = {jun}, publisher = {Elsevier {BV}}, volume = {6}, number = {6}, pages = {752--758.e1}, author = {B{\'{e}}r{\'{e}}nice Batut and Saskia Hiltemann and Andrea Bagnacani and Dannon Baker and Vivek Bhardwaj and Clemens Blank and Anthony Bretaudeau and Loraine Brillet-Gu{\'{e}}guen and Martin {\v{C}}ech and John Chilton and Dave Clements and Olivia Doppelt-Azeroual and Anika Erxleben and Mallory Ann Freeberg and Simon Gladman and Youri Hoogstrate and Hans-Rudolf Hotz and Torsten Houwaart and Pratik Jagtap and Delphine Larivi{\`{e}}re and Gildas Le Corguill{\'{e}} and Thomas Manke and Fabien Mareuil and Fidel Ram{\'{\i}}rez and Devon Ryan and Florian Christoph Sigloch and Nicola Soranzo and Joachim Wolff and Pavankumar Videm and Markus Wolfien and Aisanjiang Wubuli and Dilmurat Yusuf and James Taylor and Rolf Backofen and Anton Nekrutenko and Björn Grüning}, title = {Community-Driven Data Analysis Training for Biology}, journal = {Cell Systems} }

Do you want to extend your knowledge? Follow one of our recommended follow-up trainings:

Questions:

Questions: